A Perambulation

Dé Céadaoin 11 - Dé Sathairn 21 Eanáir 2023

September 07 - November 04 2018

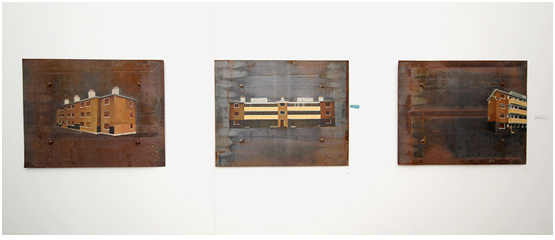

Recent NCAD graduate Sean O’Rourke draws his inspiration from Dublin’s south inner city where he has lived all his life. In 2016 Sean was awarded the NUI Art & Design prize for his triptych entitled Crucifixion, which commemorated the demolition of Dolphin House flat complex. He is based at Clancy Quay Studios.

James Merrigan interviewed Sean O’Rourke in advance of his exhibition opening at the LAB.

Sean O’Rourke has been repurposing materials found in Dublin’s inner city flats for his paintings and sculptures since art school. A graduate of the National College of Design in 2016, references to art history abound in his work, from Francis Bacon to Gerhard Richter. But it is his self-reflexive critique of society against the rusty patina of his work that comes to the surface.

"On first seeing Sean’s work online and reading his artist statement, I knew I needed to meet him and his work in person. On meeting Sean I knew that an interview would be a more appropriate discursive platform to give voice to some of the social tensions he felt were emerging from his work in the lead up to his first solo show at The LAB, Dublin."

James Merrigan: Your work comes from a place of autobiography, but the environment you have been reflecting on and extracting materials from for your painting and sculpture since art college, Dublin’s inner city flats, are not precisely the backdrops to your life? Tell us a little about your relationship to these environments.

Sean O’Rourke: Well yes, my work is autobiographical to a certain extent. What connects me to these areas is the fact I live in Dublin's inner city. I have always been attracted to the rough, rundown elements associated with Dublin's inner city. When I was younger, I would unconsciously gravitate towards these elements, but now I approach them in a more conscious manner, as an artist, looking at how these elements can play a factor in influencing our personality.

When first starting this project I would wander the inner city streets wanting to take reference photographs of anything to do with this rough aesthetic. When narrowing my search I found these elements more concentrated in derelict flat blocks. The thing that interests me the most about these flat complexes is the rusted metal borders on the windows. They're like abstract paintings in themselves – each one having their own individuality while still conforming aesthetically to the environment as a whole.

JM: How do you mean the “rough” elements of these flat complexes “factor in influencing personality”? Architectural determinism? Or is it more gender specific? Personal?

SO’R: Our environment, whether socially or physically, has a huge influence on us as people. It can determine the persona we project outward onto the world, not just in the flats, but in the whole of society. We all can easily conform to the stereotype of our environment if we are not fully conscious of the reasons why we might adapt this stereotype. I use these rough elements as a way of looking at the stereotype of young, working-class males in particular. It's also about how society profiles people. Generally the most insecure will adapt the stereotype of the tough, working-class male, using it as a shield to mask feelings of vulnerability. I know this because I have definitely been guilty of this myself in the past.

JM: In one sense, in French philosopher Jacques Rancière’s terminology, you are ‘redistributing the sensible’: making visible (and making audible in this interview) the external stereotypes of this particular social class, in an environment that is all about being in touch with one’s senses, the art space. There’s a vulnerability in that, isn't there, especially in your use of the word “shield”? How do you think someone from the flats, or one of your childhood mates would think or feel on seeing your work in The LAB?

SO’R: Yes, there is always vulnerability in putting yourself and your opinions out there. I find that by making yourself vulnerable and exposing certain feelings openly, that you begin to remove your social facade, and perhaps get closer to your true self. But obviously this is not an easy pursuit, as there are so many factors that influence our behaviour (our family, friends, environment, education, just to name a few). So we tend to not act outside the lines of our social groups because of this fear of being vulnerable to criticism, as well as the legit concern of being isolated. But it's the vulnerability we face within ourselves, the feelings that comes with that vulnerability that can be quite violent and overwhelming, so we choose not to examine it, and instead we conform to wearing our social mask, to "shield" our feelings.

As I have said before, I have noticed this in young men in particular (as well as in myself). Instead of being vulnerable people will act and behave according to their social group, hiding feelings of anxiety, fear, shame and sadness, as this would make them appear weak, masking it with a rough exterior, to the point that they are also willing to hide the fact that they are, underneath, a ‘nice guy’.

As for how someone from the flats might think or feel about my work. It's hard to generalise, but I think visually they may appreciate the work, but for some the conceptual side of the work might be looked at as a critique of people from the flats, but this is not my intention. I can see how my work could be easily misinterpreted. The work is, however, a critique of society. But because of where the materials come from, it’s linked back to the flats.

You see I don't like being put into a box, and it's funny because this is exactly what the work is about, how we are put in boxes within society. But I feel that my work and its concepts will be synonymous with the flats because of the rough aesthetic I choose to use. As for my childhood friends, again visually I’d say they would appreciate it; conceptually, I'm not so sure. Some might find it weird to talk about such issues. For others, that are more open and honest with themselves, I feel the work will strike a chord within them, and they'd know exactly where I am coming from.

JM: The ‘group’ is something that pops up repeatedly in your work as diptychs, triptychs and group portraits. Seen altogether you could call this an evolving community, with you the artist at the centre, as maker and presence, portrayed as you are as an infant and a son, a friend and a student. But you have also used the word “maverick” in terms of the individual’s unfulfilled wish to stray from the herd, from the community. There's a push and pull here between community and individuality, one conditioning the other. So how do you view the artist, whom we could describe as a ‘maverick’, in terms of community?

SO’R: I use the group portraits as a way of looking at the key elements that build our personality: family, friends, education, and the metal plates symbolising physical environment. I feel that artists, because they are influenced by so many factors, bounce between social groups, both fitting in everywhere and nowhere at the same time. So yes, the artist could be referred to as a “maverick” due to an input of diverse experiences. But if the "maverick" is shaped by their experiences, aren't they just conforming to certain elements of each social group? Which leaves me asking whether the maverick is a maverick at all, or just a merely conforming to a multitude of external factors, like the community. This is the dilemma I am left with.